My soldering iron, my collection of spare electronic components and related tools had been stored away in the basement for years. Way back, I really enjoyed tinkering with those, but when I decided to go for the software engineering aspects of computer science I somewhat lost interest. So many things to try and so little time to spare. Also, I have been lacking the room to set up a suitable work space.

As with many other IT people of my age, my first “real” computer was a second-hand Commodore 64 that my parents bought for me in the mid-eighties. I absolutely loved that machine and spent countless hours in front of it, teaching myself it’s Basic and Assembler dialects. Even though I bricked the C64 a few years later, trying to install a self-designed relay card and replaced it with a C128, I could not bear parting from the Commodore hardware. So I stored the computer and it’s peripherals in card board boxes in the attic many years ago.

Spring 2009: By chance I stumbled across Ben Heckendorn’s blog where he describes how he created his Commodore 64 original hardware laptop. I really admired his work and I really wanted such a portable for myself! Ben integrated a 1541-III DTV into his construction to replace the traditional 1541 floppy disk drive, which of course would not have fit into the laptop. Using the 1541-III connected to the normal serial bus of the C64, it allows you to mount and read d64 disk images from ordinary MMC or SD memory cards. Awesome!

Googling around, I discovered that by now there are actually several different solutions that offer this feature. There are the afore mentioned “cousins” 1541-III DTV and 1541-DTV, both based on PIC micro-controllers. The design has later been ported by Lars Pontoppidan to an AVR micro-controller, which he called the MMC2IEC. The MMC2IEC hardware and firmware has been extended and improved by a bunch of other people and evolved into the SD2IEC. Finally, there is the 1541 Ultimate that reportedly does a good job of fully emulating the original 1541. As a result, it should be able to support even copy protected games and other software that comes with their own fast-loader routines. Unfortunately, the 1541 Ultimate is also rather expensive.

AntaBaka has done a great job of collecting and summarizing the evolution of the SD2IEC on his page, which is available in German only, though. It was when I read that page that I decided I wanted to build one of those SD2IEC myself. It would be a nice project to play around with the AVR micro-controllers that I kept reading about for some time on sites like Hack-a-Day and Makezine. And it would be a great excuse to dig out the old stuff I had hidden in basements and attics.

I also liked the idea of trying to save my old Basic and Assembler programs from oblivion, petty as they might be. My old discs had been been stored in the attic along with the hardware. They had to endure extreme heat in summer and cold temperature in winter for about 15 years. Would there be anything left to save? Or would even the disk drives be decayed and broken by now? To cut at least that long story short: my trusty old C128 was working fine when I pulled it from it’s card box. And the two 1541 were happily loading the randomly chosen disks I tried them with.

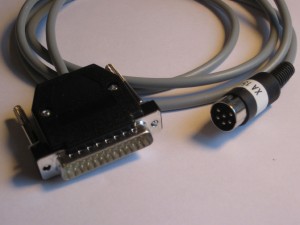

So, the first step would be to get the data from those discs and store it in d64 disk images on my PC’s hard drive. There are a bunch of different cables and adapters that can be used to accomplish this. The xu1541 appealed most to me because it is “legacy free” (what irony!), bridging between the USB port and the Commodore IEC serial port. Also, it is based on an AVR micro-controller.

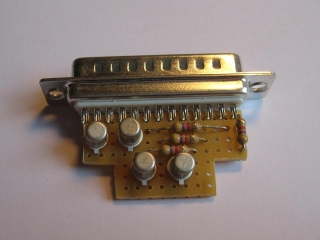

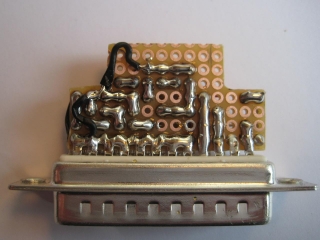

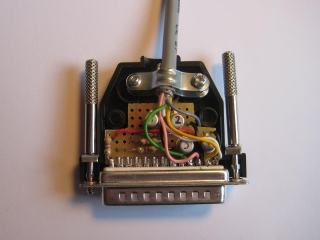

But at first, I was a little afraid I could be wanting more than I could handle. So I decided to revive my tinkering in electronics with the simpler design of the xa1541 adapter which connects the 1541 disk drive to the parallel port of the PC. We’ll hear about that another day.

Then, a few month ago, a

Then, a few month ago, a